The Attention Economy: What The Social Dilemma Reveals About Big Tech’s Business Model

Source - Amnesty International

The Rise of the Digital Dilemma

When the Social Dilemma hit Netflix in 2020, it wasn’t just a documentary: it was a wake-up call. Viewers around the world suddenly saw the inner mechanics of their favorite apps exposed. The film featured former engineers and executives from Google, Facebook, and Twitter, who described how these companies turned simple tools for connection into complex profit machines.

The genius was in the business model. Social media isn’t built on selling subscriptions or physical products. Instead, the product is attention. Every scroll, like, and share generates data that can be sold to advertisers eager to predict what users will do next. Just as Airbnb turned spare bedrooms into revenue, tech companies turned human behavior into currency. In 2023, Meta earned over $130 billion in advertising revenue, almost entirely from this invisible economy.

How the Model Works

At the core of social media’s profit engine is one thing: data. Every search, pause, or photo liked helps build a detailed psychological profile that tells advertisers who a user is, what they believe, and what they might buy. According to Amnesty International (2020), this “surveillance-based business model” converts human experience into digital capital. The longer users stay online, the more valuable that data becomes.

Algorithms continually learn from these patterns to keep users engaged. They decide what posts appear, which videos autoplay, and which emotions are triggered. The goal isn’t to inform or inspire, it’s to retain. When engagement is the metric, outrage and shock often outperform

calm and reason. The result is a cycle where users are pulled deeper into the feed, while companies quietly profit from their attention.

The Product Is You

One of the film’s most quoted lines came from technologist Tristan Harris: “If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.” It’s a chilling reminder that what seems free often comes at the cost of privacy and autonomy.

The film also highlights a line that you don’t see much: “There are only two industries that call their customers ‘users’—illegal drugs and software.” The comparison fits: like addictive substances, social media platforms rely on variable rewards and psychological triggers to keep people returning.

According to the NYU School of Global Public Health (2020), these patterns have contributed to rising rates of depression and anxiety, especially among adolescents. Prevaling scientific sentiment—drawn from data from numerous studies— argues that the more time teens spend on social platforms, the more likely they are to report loneliness, poor sleep, and reduced self-esteem. While these apps promise connection, they often deliver comparison, and the constant cycle of scrolling and validation can take a heavy mental toll.

Source - Medium

Profits vs. Principles

When The Social Dilemma premiered, companies like Facebook (now Meta) quickly pushed back. They claimed the film painted an unfair picture, arguing that they had made major progress in areas like misinformation control and privacy settings. Facebook stated that it had “made significant investments in keeping users safe and informed.”

Yet the numbers tell a different story. Advertising still accounts for over 97 percent of Meta’s total revenue. As Amnesty International (2020) points out, so long as profit depends on attention, change will remain limited. The very design of these platforms rewards what keeps users

engaged, not what keeps them healthy. A company cannot simultaneously maximize engagement and protect well-being without fundamentally altering its business model.

A Health Crisis in Disguise

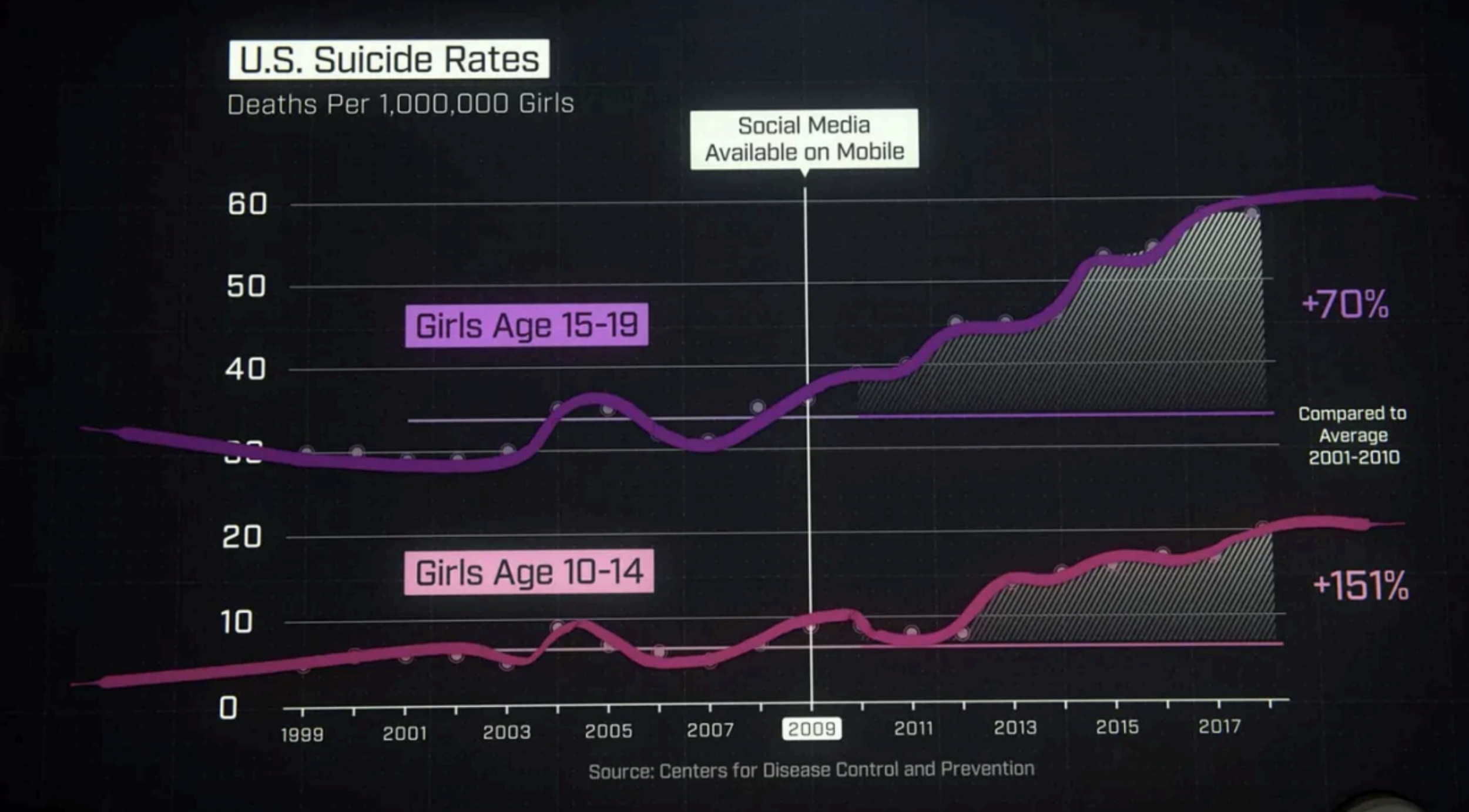

The NYU Public Health report describes social media addiction as a “public health concern.” It connects increased online engagement to spikes in anxiety, sleep problems, and body image issues. Since the rise of social media around 2009, suicide rates for girls in the United States

have climbed dramatically, increasing between 70% and 151% depending on age group, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During the pandemic, misinformation about masks and vaccines spread faster than factual health updates. The same algorithms that serve ads for sneakers also push content that divides communities and undermines trust. The film illustrates that algorithms don’t possess the objective truth, but rather what generates increased engagement. Falsehoods and outrage are simply more clickable. In the attention economy, accuracy is optional, but engagement is everything. As one former executive in the documentary says, “The system is not broken—it’s working exactly as designed.”

Source - Medium (CDCP)

The Push for Regulation

Critics argue that ethical tweaks won’t fix a business model built on manipulation. Amnesty International (2020) calls for an end to surveillance-based advertising altogether, saying it violates privacy and human rights by default. Governments around the world are slowly catching up. The European Union’s Digital Services Act aims to make algorithms more transparent, and the U.S. has seen growing debate over data privacy laws.

Still, as Forbes (2020) points out, dismantling the engagement economy won’t happen overnight. The article argues that the future may lie in “human-centered design,” where

platforms profit through trust and meaningful connection rather than attention extraction. It calls for companies to shift toward models that emphasize transparency, subscription-based access, or decentralized control. The business world is watching closely. Tech leaders who can align ethics with profitability could define the next era of digital innovation.

The Future of the Attention Economy

Artificial intelligence is already transforming how platforms operate. Social media companies use AI to personalize feeds, predict trends, and moderate content. Some also use it to target ads more precisely than ever before. Yet, just as Airbnb faced the question of scale without losing its human touch, tech giants now face the question of how to innovate without deepening dependence.

Tristan Harris warns that unless change happens, the next generation will inherit a world “where truth is no longer profitable.” The path forward may involve reimagining success not as more engagement, but as better engagement. Companies could reward authenticity, build transparency into algorithms, and allow users to control their own data. As Forbes (2020) concluded, “There is a way out—but it requires the same creativity and courage that built these platforms in the first place.” The future of social media may depend on whether Silicon Valley chooses connection over compulsion, and people over profit.