The $38 Trillion Question: Is the U.S. Debt a Problem?

Introduction

Since President Trump’s inauguration in January of 2024, discussion surrounding the importance of federal debt has moved beyond economic circles and into everyday conversation. Trump’s renewed focus on tariff policies raises a long-standing question in U.S. politics: Should policymakers take aggressive measures to minimize debt? Or is this extreme level of borrowing the new norm?

In a given fiscal year, if government spending exceeds the revenue it accumulates from taxes, a budget deficit occurs. To finance the deficit, the government will borrow money by selling Treasury securities, promising eventual reimbursement plus interest to investors. Thus, the national debt refers to the accumulation of repeated budget deficits that the government has yet to pay back over time.

Today, the debt stands at an unprecedented $38 trillion, which is about 120% of national GDP. While debt is often measured as a percentage of GDP, government spending only accounts for a small portion of annual GDP with its primary contributors being consumption and investment. When the debt is compared to annual federal spending rather than total GDP, the percentage becomes even more striking.

Source : Pexels

Why Economists Worry About Government Debt

From a traditional economic perspective, ongoing fiscal debt can pose several long-term issues for the economy. For one, heavy borrowing reduces the funds available for private investment, which increases interest rates and makes it more expensive for businesses to expand. This concept, known as crowding out, slows productivity, innovation, and job creation.

However, deficits can benefit the economy in the short run. Keynesian economists believe that government intervention, like increased spending or tax cuts fueled by borrowing, can stimulate aggregate demand and speed up recovery during a recession. In these cases, borrowing is not deemed reckless but rather a necessary measure to stabilize the economy.

From an economic perspective, debt becomes an issue when emergency borrowing becomes habitual. While short-run benefits may stimulate the economy out of a recession, the overall impact of accumulating debt results in long-term declines in growth.

Debt Patterns: Past Versus Present

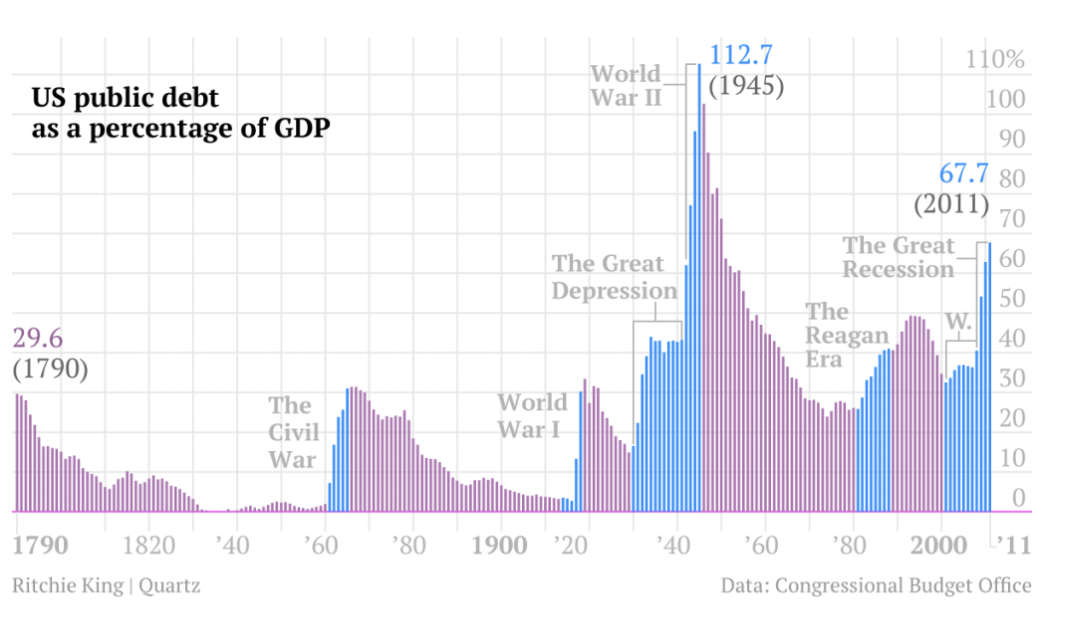

Historically, government debt levels would rise during national emergencies, like wars and economic calamities. Borrowing was deemed necessary and patriotic in these instances. Following these emergencies, the government made strong efforts to reduce the debt as a percentage of GDP.

Source: The Atlantic

In the modern world, spending patterns consistently outpace yearly revenue, demonstrating how debt no longer spikes and declines but rather continuously increases over time.

Spending on programs like Medicare and Social Security is mandatory, even as the population ages and healthcare gets more expensive. Recent demographic shifts have reduced the percentage of working-age adults and increased the percentage using retirement programs. An aging population goes hand in hand with increased strain on healthcare programs run by the government, like Medicare and Medicaid.

Recent Fiscal Policy Trends

In general, politicians tend to prefer tax cuts and increased spending to taxing citizens; they want to remain popular with voters. This logic plays a big role in the debt crisis—there’s no political incentive to make the hard choice of increasing taxes.

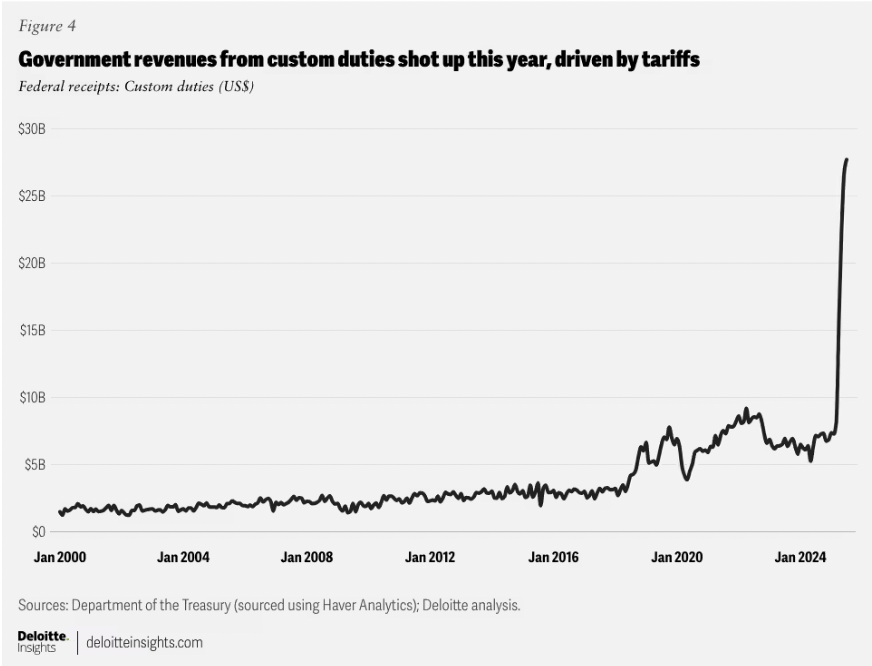

President Trump has placed emphasis on reducing the budget deficit rate, implementing his controversial, aggressive tariffs in order to reduce imports from other countries. Economically, placing tariffs on imported goods increases government revenue and can reduce the trade deficit in the short run. Tariff revenues amounted to more than $16 billion in early April as a result of Trump’s 10% tariffs on imported goods from certain countries, along with up to 145% on imports from China. However, while the tariff revenue contributes to government income, it is not large enough to resolve the underlying budget deficit.

Source: Deloitte

Recent budget options include raising the retirement age for Social Security, reducing the Department of Defense’s annual budget, or imposing a value-added tax (VAT) on a broad or narrow group of goods or services. Some implementations are projected to save up to $3 trillion in spending over the course of 10 years, which could contribute significantly to financing the debt.

The Growing Burden of Interest

As total debt rises, interest payments increase alongside it. Heightened interest provoked by accumulated debt amplifies the issue, creating a feedback loop that embeds persistent deficits into the federal budget. In recent years, U.S. interest payments have surged into the hundreds of billions, surpassing government spending on programs like transportation. This alarming statistic means that a growing portion of federal revenue is devoted to paying off not just the debt but the interest payments, which will only grow year by year if no measures are taken to balance the budget.

The Bottom Line

Ultimately, U.S. debt is not an immediate crisis, but the lack of political will to address it may be. The debt poses a growing constraint on the nation’s future. Danger does not lie in borrowing but rather in the normalization of deficits and a lack of political action to reform. If left unaddressed, rising interest rates along with mandatory spending programs will continue to crowd out businesses and limit policy flexibility. The true question is not whether the nation can borrow; it is how long the U.S. can afford to do so without consequence.