The Economic Impact of the CHIPS Act and Protectionist Tariff Exemptions

Source: Maxence Pira

84 years ago, the Permanente Metals Corporation shipyard hummed with activity. It was the peak of WWII. On Nov 8, 1942, the keel for the SS. Robert E. Peary was laid down, and in just 4 days, 15 hours, and 29 minutes more, the ship would launch into the Pacific.

84 years ago, the United States was able to launch one of these Liberty Class ships in record low times. The industrial might of the US—with its motor industry galvanized into action through war—stood in full, unmistakable display.

Fast forward to today. A new era of the Liberty Class has been announced, with the first ships to be delivered at the end of 2026. The mission profile remains similar: a hybrid cargo ship capable of moving supplies, vehicles, or troops.

Yet the ships of the future will lack the manpower that guided the previous ships around the world. Rather, autonomous systems will “sit” at the helm, driven by artificial intelligence and integrated systems with other manned Navy ships.

Even more important, the ships are being built entirely by the private company Blue Water Autonomy, a US-based company founded in 2024 by Navy Veterans. Their mission is to deliver ships faster in a method more reminiscent of peak US industrialism, aligning with the Pentagon's push for defense contractors to privately develop key military technology.

A new era of manufacturing

The most notable example of US reshoring efforts is at the core of all computers: semiconductors. The tech to invest in and incentivize today is not just the vehicles of tomorrow, but the tech that enables the systems that drive them. As PWC reports, US semiconductor manufacturing capacity has dropped from nearly 40% of global supply in 1990 to 12% today, a concerning metric.

And while these new efforts to reshore semiconductor fabs reflect the broader government policies that incentivize investment in the US, the two most recent presidencies have different approaches to providing that incentive—both of which come with different macroeconomic effects.

For former President Biden’s administration, that was the passing of the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act in August 2022. In the simplest terms, the CHIPS Act provides subsidies for semiconductor companies like TSMC, Micron, Intel, and Texas Instruments to reshore parts of their foundry operations to the US, all financed by a $52.7 billion pool of funds.

And for the current President Trump’s administration—an administration that has been a staunch critic of the CHIPS and Science Act—exemptions and credits from the protective tariffs that have defined much of the administration’s economic policy. By price shielding, domestic producers who would otherwise be undercut by lower-cost Asian fabs decide to build in the US.

These two incentives (subsidies versus tariff exemptions) have different methods of truly inspiring semiconductor companies to build in the US.

Tariff incentives impact investment from a price-side expansion. The new fabs built with tariff exemptions can sell at a higher average selling price while remaining competitive with their Asian counterparts. Higher ASPs drive gross margin expansion and project stronger EBITDA, ultimately driving a better IRR on these multibillion-dollar fabs.

Conversely, the new fabs built with government subsidies drive similar EBITDA and margin growth through cost-side compression. For companies that invest billions in very cost-intensive machinery, government subsidies can significantly lower their capital expenditure.

The impact

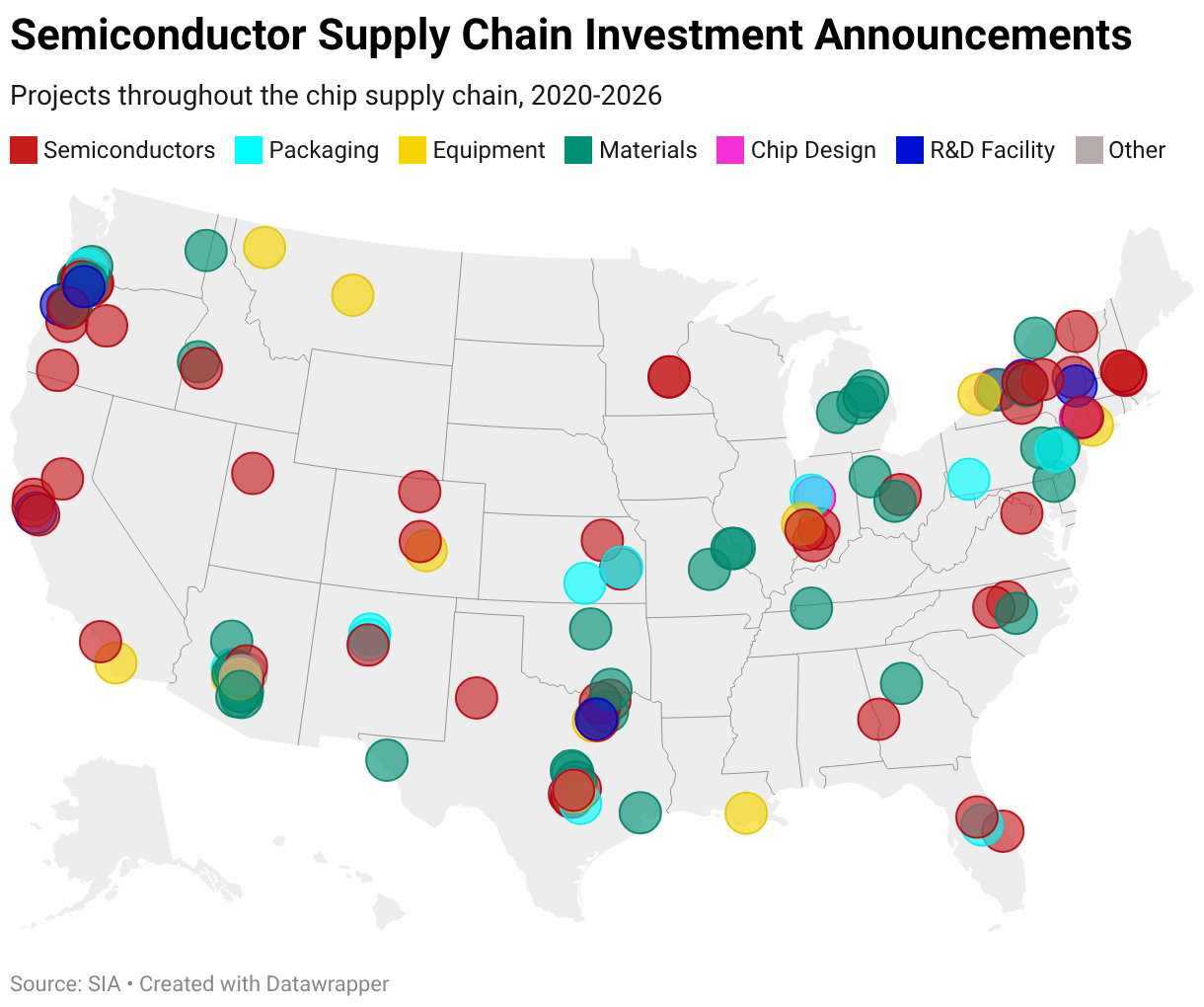

Now, with four years of the CHIPS Act being passed and over a year of the new protectionist tariffs and their exemptions, the investment pledges and economic impact projections have been vast. As reported by the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), over $640 Billion has been pledged to supply chain investments in the US across 30 states, subsidized by roughly $40 Billion in government subsidies from the CHIPS Act alone.

Source: SIA

Tariff policies have only compounded the impact of the CHIPS Act, and combined with a boom in artificial intelligence investment and geopolitical tensions that threaten a reliance on East Asian foundries, more and more companies continue to pledge money to projects.

All of this investment has economic effects on the communities that receive the investment. The development in Arizona is the best example of the regional effects of these combined efforts.

In 2024, TSMC—the world’s largest foundry—was announced as the CHIPS Incentives Award recipient. Arizona State University studied the impacts this had, describing how semiconductors are “transforming Arizona’s economy.”

First, the labor market in and around Phoenix (one of the new fab hubs in the US) is projected to add roughly 6,000 jobs to the economy, as reported by TSMC itself. The announcement of the TSMC facility also brought additional secondary construction growth in the Phoenix Metro, adding more jobs in the construction and manufacturing sectors outside of the promised TSMC jobs. Furthermore, civil, community, and residential projects historically have followed megaprojects like that of TSMC’s.

All of these investments have revitalized and reshaped Phoenix, and stepping back, Arizona’s economy as a whole. The state has typically relied on real estate, tourism, agriculture, defense, and services, with labor markets predominantly mid-skill service and construction roles. Phoenix may now begin to reverse brain drain to STEM hubs like California and Texas.

While the impact of this fab has many positive economic effects, particularly in the labor market, it is also important to note that the demand for highly-skilled workers can drive up wages and thus rents in metro areas, raising the cost of living for everyone.

This cost-of-living increase leads to another issue: inflation. As critics of the CHIPS Act argued when it was still on the Senate floor, the regional cost shocks associated with foundry investment could lead to national supply-chain repricing. The regional cost shocks not only come from rent increases, but also from utility disruption associated with the resource-intensive fabs.

All the while, the government subsidies that bolster TSMC’s investment generate a traditional demand-pull inflationary pressure. Federal grants are a form of fiscal expansion, and through multiplier effects, pull aggregate demand to the right.

While tariffs are typically considered inflationary government policy, Trump’s tariff policies may have some impact in mitigating the demand-pull inflation of the CHIPS Act.

Fabs are extraordinarily intensive, and without the tariff exemptions given to semiconductors, build costs would rise materially. Instead, there are lower upfront fab costs, which reduce the subsidy required for each project and debt issued for the build. The tariff cuts also improve the fiscal multiplier efficiency.

Phoenix is just one example of this investment at scale and the resulting economic outcomes that come with it. Again, similar investment projects for all parts of the semiconductor industry have been started in 30 states, and more will likely follow, given the current AI boom.

The future

Ultimately, the hybrid, cross-administration policy of the CHIPS Act, combined with protectionist tariffs and selected exemptions, means US semiconductor reshoring will not proceed as a purely inflationary industrial push as it has, but rather as a calibrated re-industrialization cycle. In the near term, localized cost shocks like those seen in Phoenix—tight labor markets, rising shelter costs, and utility strain—will likely persist as megaproject clustering accelerates.

Yet as capacity comes online and supply chains densify domestically, the same fiscal momentum that initially pulled aggregate demand rightward should slow down, beginning to turn into real output expansion rather than cost-of-living escalation.

In the end, a new America will emerge if all goes to plan, one that echoes the past industrialization of critical industry that drove technology and productivity for decades to follow.