Hiring N’ Firing: Europe’s Innovation Issue

Source: Tech Funnel

Paris and Berlin could produce the next trillion-dollar tech giant, but only if Europe makes failing cheaper. European labor laws make it significantly more costly to fire employees compared to the United States. In the US, firms can fire an employee at a cost of around 7 months of wages per employee. This is a completely different picture in Europe: in Germany, this number is 31 months, and 38 months in France. This doesn’t come from just severance laws (compensation and benefits given to employees when they are fired), but also through protracted negotiations with unions and notice periods. Such stringent rules lead to firms often retaining “zombie” employees whom they are hesitant to fire because of the high cost. New hiring is thus put on hold as firms wait for contracts to end and are wary of making the same pricey mistake. Europe’s protective labor laws turn restructuring into a years-long ordeal, while American firms can pivot within weeks.

How Rules Change the Bets

In the US, most employment is “at will”, meaning firms can hire and fire without many legal boundaries. Tech CEOs across Silicon Valley have embraced the “hire slow, fire fast” slogan, allowing them to scale up quickly when opportunity calls, but also cut losses quickly when projects fail. On the contrary, bosses in Europe will often have to negotiate with work councils and politicians, who may insist on costly severance packages. Some big German firms, such as Bosch and Volkswagen, have announced workforce layoffs that stretch all the way to 2030, showing how long downsizing takes in Europe. The result is that it creates a humane feeling system, preventing mass layoffs, but there are hidden costs that hinder firms’ long-term health.

What the Research Shows

When failure is expensive, companies tend to shy away from taking risks. Olivier Coste and Yaan Coatanlem, two French economists, argue that Europe’s innovation problem stems from this “failure cost” issue. Peter Garicano, a researcher from the University of Oxford, found that restructuring costs European firms ten times more, on average, than American firms. Ultimately, this leads to the scenario in which many bold investments that make sense in America wouldn’t be worth it for European companies when you take failure costs into account. Economists have observed that countries with stricter firing laws tend to shy away from high volatility and high-tech sectors. A study by the Silicon Continent finds that “the extent to which a country can benefit from new technologies” is reduced significantly with such laws, leading them to stick to safer improvements, such as a better “turbine or shampoo”, rather than aiming for new innovations.

Europe isn’t inherently less visionary; they are just responding rationally to the high price of failure. US firms like Meta, Google, and Apple thrive in high-risk projects due to easy firing. For example, Apple hired hundreds of engineers for a self-driving car project but fired 600 of them in 2024 after the plans fell through. Apple isn’t alone, though, as American tech giants have fired tens of thousands of workers in recent years. CEOs such as Satya Nadella, Microsoft CEO, has even attributed firing to be the “enigma of success”. Strategic firings are what have allowed US firms to quickly reallocate talent and capital to new opportunities, allowing pivots from a failed venture to a new generative AI or invention. In an environment where that firing power is reduced, that leads to fewer big swings coming out of Europe. Such regulations pose a big concern for American venture capitalists. In one instance, The Economist published an article about a Boston VC fund pulling out of a French-founded startup when the founder moved operations back to France because of the risks associated with firing costs and rigidities. In the end, Europe not only has less domestic risk-taking but also has a harder time attracting foreign capital for bold startups.

Source: European Central Bank

By the Numbers—Scale and Outcomes

The long-term effects of these policy differences are very clear. In 1995, Europe and the US were roughly equal in productivity, with around $46-47 in GDP produced per hour of labor. Since then, though, Europe has lagged while the US has soared ahead in productivity and innovation. Between 1995 and 2019, the US saw labor productivity rise by 50%, while Europe only increased by 28%. This is in part due to the digital and tech revolution, which the US has dominated with firms like Apple, Meta, Amazon, and Tesla, which are all companies that are able to scale up and down aggressively according to what best suits their interests and profits. Many of Europe’s blue-chip corporations are the same companies that have led for decades. While there is some innovation, European markets center around incremental improvements to

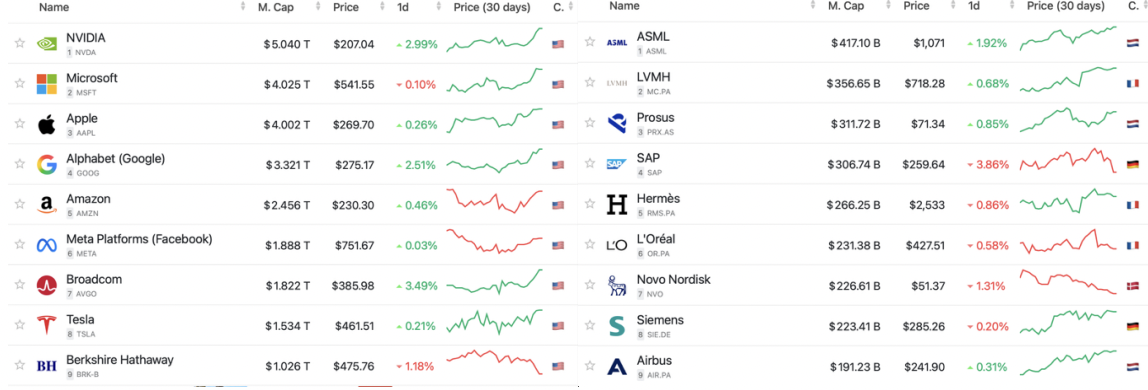

20th-century products, while American firms are coming out with technologies such as AI, which wouldn’t have been thought possible just a few decades ago. Nvidia alone, a California-based chipmaker reaching a valuation of over $4.5 trillion, is worth more than the 20 largest listed companies in the entire EU combined. Keep in mind, Nvidia is one of the several firms in the trillion-dollar club.

Source: U.S. mega-caps dominate global market value

Europe, on the other hand, hasn’t even produced a single trillion-dollar firm, or even passed a $450 billion valuation. Another telling metric is that the US is home to over 50% of the world’s “unicorns” (startups valued at over $1B), while Europe accounts for less than 10%. It must be said, Europe doesn’t lack creative entrepreneurs, but rather, many European founders end up moving to the US for more abundant venture funding and a relaxed firing environment. The US venture capital industry is around 6 times larger than Europe’s ($270B vs $44B). This capital gap is a direct reflection of behavior of investors due to strict labor regulations and high firing costs. Venture capital thrives in an environment in which a startup can pivot, downsize, or shut down efficiently if needed, and the US has just that.

The Trade-Off and Better Middle-Path

To be clear, labor flexibility has cons, too. America’s firing policies lead to US workers with far less job stability, weaker unions, and often minimal safety nets. This leads to Europe facing the challenge of balancing the innovation benefits of flexibility without entirely sacrificing its workers' protections. One solution Coste and Coatanlem posed is to differentiate by worker type. This could be by having less protection for highly paid tech workers who don’t need protection as much, and more protection for lower-wage or more vulnerable workers. Another solution could be following Denmark’s “flexicurity” model: pairing flexibility with generous unemployment benefits, retraining programs, and strong safety nets. The Netherlands and Sweden have also started to lean into this model and have found high rates for both innovation and worker satisfaction.

It is important to note that there is an economic incentive for Europe to reform: increasing innovation will lead to a sustainable social model in the long run. Having higher productivity and growth will lead to an increase in funds for public services, welfare benefits, and living standards. If Europe keeps on lagging behind, this could lead to a shrinking of global influence, which will cause budgetary pressures on its welfare states, but this is where smarter labor laws can help. A recent policy brief found that if countries like France, Italy, or Spain shifted to a US-style employment approach, it could boost R&D investment by up to 50%, as well as a 1% boost to annual productivity growth.

In the end, an economy’s strength lies in how well people feel empowered to be productive and innovate. The US keeps highlighting how a fearless approach to creative destruction can lead to massive financial gains, but is now facing the social fallout of inequality and job insecurity. On the other hand, Europe shows it’s possible to keep worker dignity but is facing the economic fallout of slower growth. The solution lies between both ends of the spectrum: a system in which firms have the courage to take risks and workers have the

confidence of not being left behind. As Europe looks to find a perfect medium, it should find inspiration within its own borders, but also across the Atlantic, and maybe, just maybe, the next trillion-dollar firm will sprout in Paris or Berlin, not just Palo Alto.