Germany’s Reluctant Investors Start to Embrace Stocks

Source: Adobe Images

When Money Became Worthless

German wariness toward financial risk traces back to the hyperinflation of the early 1920s. After financing World War I by borrowing and printing money instead of raising taxes, the country was left with crushing debts. The Treaty of Versailles added to the burden, imposing reparations of 132 billion gold marks, equivalent to more than $500 billion today. By late 1923, the Papiermark (Germany’s currency at the time) had collapsed to the point where one U.S. dollar was worth nearly 4.2 trillion marks. Prices soared so fast that bread or meat cost billions, while bank deposits and government bonds became worthless. Families scrambled to exchange cash for tangible goods such as diamonds, art, or real estate. Stability returned with the Rentenmark, introduced in November 1923 in strictly limited supply, but trust in money and financial institutions had been deeply scarred.

A generation later, another currency collapse followed World War II, though for different reasons. By the end of World War II, the Reichsmark, the official currency since 1924, had collapsed in value. Years of unchecked money printing to finance the war, coupled with destroyed factories and empty shops, left Germans relying on barter and black markets instead of cash. To reset the economy, the Western Allies introduced the Deutsche Mark in June 1948 across their occupation zones, generally replacing the Reichsmark at a rate of 10 to 1. The reform restored confidence with goods reappearing in shops, and the black market diminished. It laid the foundation for West Germany’s postwar recovery, but also reinforced a culture of caution toward financial risk that endures today.

Source: News Dog Media

A Nation of Savers Slowly Turns to Stocks

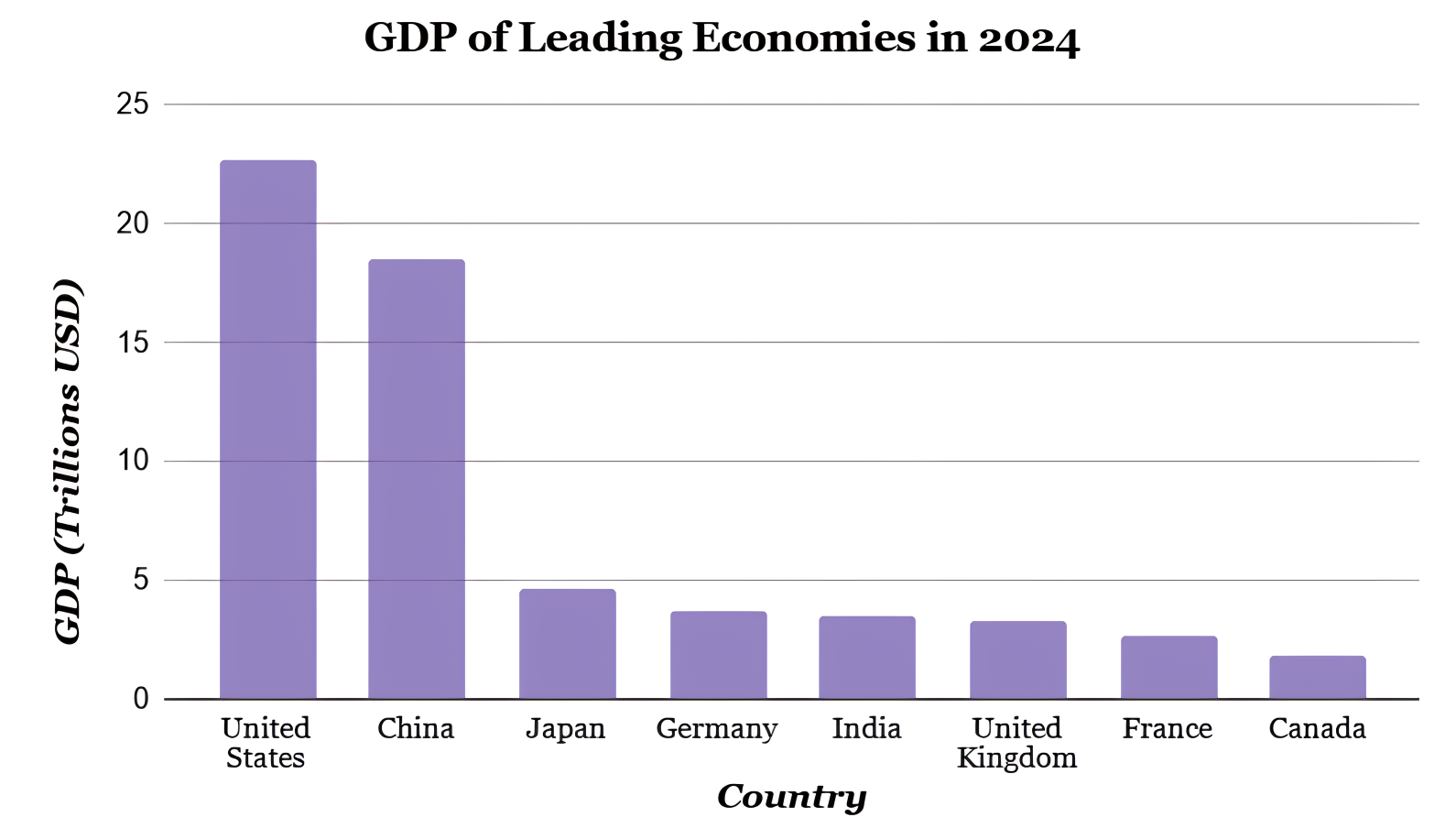

Yet, despite this aversion to equities, Germany still grew into one of Europe’s most resilient economies, with a GDP of approximately $4.66 trillion in 2024, ranking as the world’s fourth-largest.

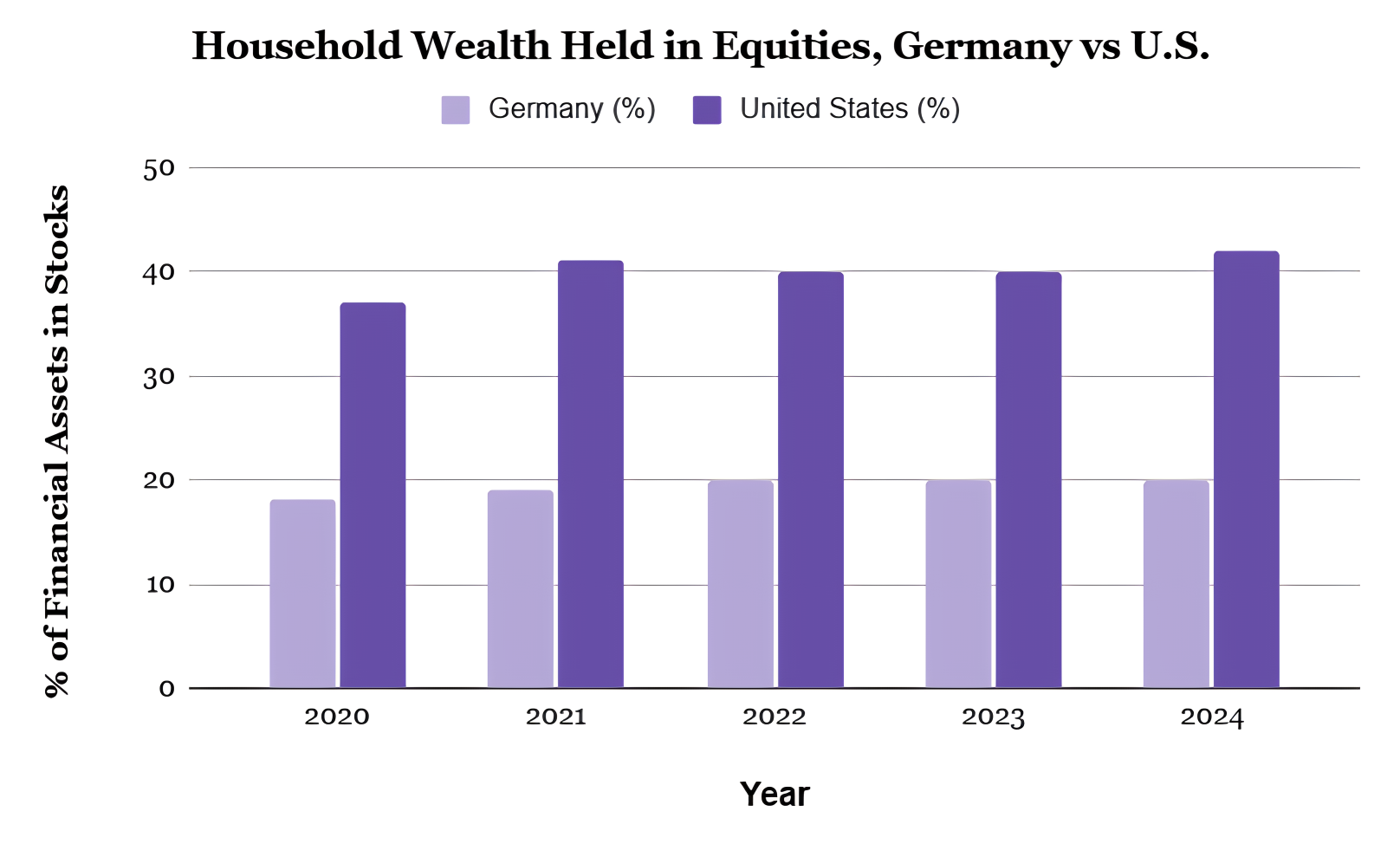

Now, that long-standing wariness is beginning to crack. A record 12.1 million Germans now invest in equities through stocks, funds, or ETFs, representing a 44% increase from a decade ago, including three million new investors in just the past three years. Despite the bullish trend of the past decade, only 20% of German households own stocks, compared with 42% in the United States.

Rising investor participation, both from German and foreign sources, coupled with increasing flows into low-cost ETFs, has added fresh momentum to the DAX, Germany’s flagship stock index, which has climbed 22.37 percent year-to-date, significantly higher than the U.S.’s S&P 500, which is currently at 10.2% YTD.

Part of the rally’s strength lies in the index’s international character. Many of the DAX’s largest companies are global multinationals that dominate the index. Around 80 percent of their revenues are generated internationally, and 52.6 percent of the index’s share capital is held by foreign investors. This global orientation has enabled DAX firms to thrive even as Germany’s domestic economy has stagnated, with GDP growth remaining flat in the most recent quarter.

Another catalyst behind the DAX’s record growth is the European Central Bank’s pivot from rate hikes to cuts, a traditional tailwind for equities, since lower borrowing costs spur investment and make stocks more appealing than bonds. The dollar’s weakness has also made the DAX and foreign assets more broadly more attractive to U.S. investors, as gains in euros translate into higher dollar returns when repatriated.

The Price of Playing It Safe

Even as more Germans dip into stocks, their household balance sheets remain bank-centric. Of the money set aside after consumption spending, 36.91% sits in bank accounts, albeit safe and low-yielding, compared with just 11.17% in the United States. Americans direct most of their spare wealth into retirement plans, mutual funds, and equities, vehicles that historically generate higher long-term returns. The split highlights two contrasting habits: Germans still value safety and liquidity, while Americans tend to prioritize building wealth through capital markets.

Data Source: OECD

Data Source: World Bank Group

Yet the ground is shifting. Germany’s aging population is stretching the pension system, and pension funds and insurers have long relied on Bunds — the government’s bonds — for steady income. But in 2016, and again from 2019 through early 2022, 10-year Bund yields fell below zero, meaning investors who bought at those prices were guaranteed to get back slightly less than they paid if they held to maturity. The unusual outcome reflected extraordinary demand: the European Central Bank was buying large volumes of Bunds to stimulate the economy by lowering interest rates and thus encouraging borrowing and spending. For many big institutions, accepting a small loss was like paying a fee to store money in the safest vault in Europe. They still needed Bunds to meet regulatory requirements, to keep portfolios liquid, and to protect capital from the larger losses that riskier assets might bring. That’s why demand stayed strong even when yields slipped below zero. Yields have since rebounded above 2.5% in 2025, but the years of negative rates eroded confidence in traditional savings and nudged more Germans toward equities.